Written By Yuri Andrei B. Morrison | December 17, 2025

Features

Written By Yuri Andrei B. Morrison | December 17, 2025

WHEN a viral content creator releases a children’s song about consent, it should be lauded for its purpose. “Pribado” by famous content creator Toni “Mommy Oni” Fowler tackles the uncomfortable but urgent need to teach kids about private parts and personal space. Yet the message doesn’t exist alone; it’s tied to the digital world surrounding its creator.

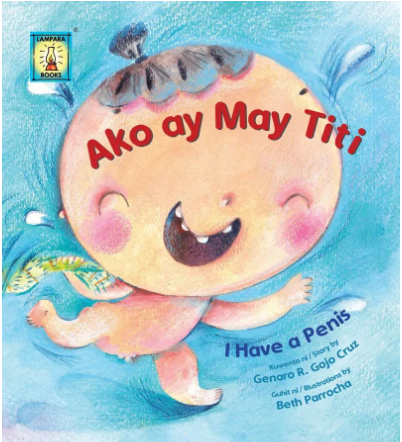

“Ako ay may titi”— a phrase that first made me raise an eyebrow before I ever understood its premise. Hearing the title alone was enough to raise questions. I thought it was yet another adult meme passed around online, especially with how the internet tends to twist anything remotely anatomical into innuendo. What made it stranger was its packaging: bright colors, a cartoonish cover, and the thinness of a children’s book. It felt contradictory, like a joke disguised as a nursery read.

But as conversations around consent and child safety continue to evolve, titles like these reveal a deeper purpose: calling body parts exactly what they are, instead of hiding them behind euphemisms, especially when the people who might need to use those words are children trying to ask for help.

Calling it what it is

Toni Fowler’s song “Pribado” functions on the same logic. The track explicitly names private parts — lips, breasts, buttocks, penis, and vagina — and lays down the simplest rule: no one should touch them.

But the song goes further. It lightly but clearly hints at actions young victims of sexual abuse ignorantly tolerate, encouraging them to tell a parent or trusted adult if something or someone makes them uncomfortable. For many, this is where proper naming becomes crucial. Children who know the correct terms are more easily understood and more likely to be taken seriously when they report inappropriate behavior.

Body literacy is both a shield and a language.

Juxtapositious Wisdom

In the second episode of her podcast, Fowler’s Position, Fowler talks about the origin of her career and the hardships that shaped both her and Papi Galang, who have backgrounds in nightlife-related work. Their experiences growing up, riddled with instability, vulnerability, and a lack of proper guidance, are the very reasons they emphasize teaching children early about boundaries and consent.

Their advocacy, as inconsistent as their public personas may appear to some, is rooted in lived reality. They echo a kind of generational course correction: We went through these experiences. Our kids shouldn’t.

Now, I don’t normally like dipping into the daily lives of others, and that’s the whole premise behind vloggers, but this is where Fowler’s voice becomes important. Her message isn’t academic or technical — it’s accessible, direct, and delivered in the language many Filipino parents and children actually use at home.

A Dissonant Motion

Still, despite the song’s important message, the execution of the music video raises questions. In the section discussing the buttocks, Fowler is shown twerking. A choice that feels at odds with the line she’s trying to draw between respecting private parts and avoiding unnecessary exposure of them.

On one hand, it could be interpreted as a reclaiming of her image. On the other, it risks diluting the educational intent, especially for children who may focus more on the visuals than the message. The contradiction doesn’t erase the advocacy, but it does introduce friction, possibly distracting younger viewers from what they should be learning.

That friction leads us to a bigger issue, one that has less to do with the video itself and more to do with the ecosystem around it.

The audience

While “Pribado” is clearly marketed for children, Fowler’s broader online presence is not. Platforms like YouTube use algorithms that prioritize engagement, not safety. A curious child who clicks on “Mommy Toni Fowler” for an educational song may be immediately guided toward her other content — which is saturated with adult themes, strong language, and vices that many parents would not want their children consuming.

For an unfiltered child viewer, one tap can collapse the boundary between “educational message” and “adult reality.” Even if Fowler’s life is her truth, it does not align yet with what young viewers should be exposed to.

This is not a moral indictment; it’s an algorithmic one.

Accessibility is both a blessing and a danger.

An overall rating

Ultimately, “Pribado” is a step forward — but one that still requires parental guidance, content filtering, and conversations at home. In the end, it can open the conversation, but it is the adults around children who must ensure that the spaces they learn from remain safe, guided, and grounded in intention.

The music video helps, but the surrounding platform complicates it.

As idealistic as we want things to be, awareness campaigns don’t exist in a vacuum.

Volume 31 | Issue 6