Written By Sianne Liamm F. Eridani | September 30, 2025

“Nonetheless, we hold on,” Cumpio’s Unjust Detention

WHAT would you do if the very governing body tasked with protecting its citizens were the one purposefully incriminating you because of your profession or the work surrounding it? For some, this is only a troubling thought, but for others, it is a harsh reality. Take Frenchie Mae Cumpio, an investigative journalist unjustly detained in Tacloban City Jail for five years until today.

Cumpio, a former CEGP Eastern Visayas Coordinator, along with human rights activists Mariel Domequil and Alexander Abinguna, was arrested in February 2020 for alleged possession of illegal firearms and explosives after a pre-dawn police raid at their domiciles. The arrest came days before Cumpio told the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility that masked men had been tailing employees from Eastern Vista, the online community media outlet where she serves as the executive director. According to authorities, Eastern Vista served as a front for the New People's Army, the armed branch of the Communist Party, accusations that the activists vehemently deny.

Apparent inconsistencies from these charges were found by the international organization known as Reporters Without Borders (RSF).

Symbolic of this is a striking photo, taken by police during Cumpio’s Feb. 7, 2020 arrest, that shows an officer staging the discovery of a Communist Party of the Philippines flag, a .45-caliber pistol, and a grenade on the young woman’s bed. As per Cumpio, she recounted screaming when she saw the items placed on her bed during the police search, implying that the evidence had been planted.

“The clumsiness with which the charges were built—and sometimes fabricated—against this young journalist is shocking. From dubious police methods to testimonies riddled with inconsistencies, this investigation exposes the emptiness of the accusations and the total impunity of those who brought the charges, without even attempting to be credible,” says Arnaud Froger, Head of RSF’s Investigation desk.

One of the most disputed elements of the case—denounced by UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression Irene Khan as nothing less than a “parody of justice,” are the testimonies of two alleged former rebels whose statements have appeared in multiple cases and whose inconsistencies cast serious doubt on the prosecution.

One witness, “Marjie” claimed to have handed money and ammunition to Cumpio and her roommate in 2019, yet provided no corroborating evidence and even contradicted herself by placing Cumpio at rebel meetings as early as 2008, when the journalist was only nine years old.

The second, “Alma” admitted she had seen Cumpio only once in 2016, later revising her account under oath without substantiation, while also acknowledging she became a state witness after 17 criminal charges against her, including murder, were suddenly dropped. Both women are under military protection or benefit from cooperation with authorities, raising further concerns that their testimonies—central to the case—were manufactured to justify the journalist’s detention.

Beyond these accusations, RSF found that weeks before Frenchie Mae Cumpio’s arrest, the police inconspicuously submitted another report linking her to the murder of two soldiers in her hometown, which took place in October 2019 near Sumoroy, Northern Samar.

Nearly five years after the report was filed, the case has seen little progress, and the journalist only learned of the murder charges a few months ago. It remains unclear who initiated the case, but what is evident is how unsubstantiated the allegations appear—much like the charges she is currently battling in court.

With all of the charges taken into account, Frenchie Mae Cumpio faces up to 40 years of imprisonment.

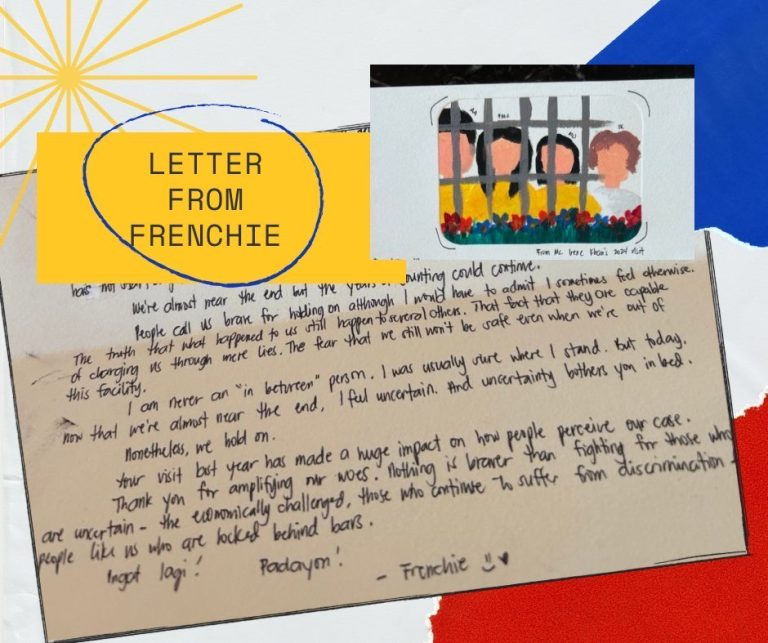

A handwritten letter by Philippine journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio, who has been held in prison for more than five years, that was delivered by CPJ from her prison in Tacloban City in eastern Philippines to U.N. special envoy Irene Khan in Geneva on June 24, 2025. (Photo Courtesy of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines).

“PEOPLE call us brave for holding on, although I would have to admit I sometimes feel otherwise,” says the 26-year-old journalist in a handwritten letter delivered to U.N. special envoy Irene Khan last June 2025.

Though hope is not lost, Freedom Now and the International law firm Dechert LLP filed a petition in September 2025 with the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention on behalf of the three activists. And in Cumpio’s words:

“Nonetheless, we hold on.”

Cumpio is one of many media workers and journalists whose rights were squandered through the government’s continuous censorship and red tagging, a familiar tune with the recently passed anniversary of Martial Law last Sept. 21 in which 70,000 social activists, students, church workers, and journalists were unduly arrested.

This year, Sept. 21 not only served as a date to commemorate Martial Law but also a day of protest and nationalism amid the egregious corruption of government sectors such as the DPWH. Amid the memeable banners, political performances, and celebrity appearances, press censorship remains rampant, even at “peaceful protests.”

Zedrick Madrid, a student-journalist from Far Eastern University (FEU) detailed in a Facebook post his infuriating experience in one of his coverages in the Sept. 21 rally. He recounts that a police officer was pulling his shirt because he was trying to take a photo of police brutality being done to a protester.

“There were five to ten police officers around the protester with riot shields and arnis. Unfortunately, aside from the five to ten surrounding the man, I was also encircled,” his post read.

Although he identified himself to the police as a member of the media, the photojournalist was still hit with a riot shield and repeatedly struck on the head, shielded only by his helmet.

53 years have passed since Martial Law, yet incidents of press censorship and oppression never truly went away. This speaks volumes. Crimes against the press are not isolated cases but a systematic, politically ingrained practice that undermines democracy.

Stories such as Cumpio’s or Madrid’s remind us that the struggle for press freedom is far from over. Their story stands as both a warning and a call to action—that in a nation where truth is often stifled, the duty to defend journalists and uphold the people’s right to know becomes more urgent than ever.